Variability is key (sprinting, jumping, lifting)

In this series, I am detailing the goal of our summer: train like cats to become more like cats—built on the pillars of functional variability and a quick central nervous system (CNS). Welcome to part three. In this post, I want to dig into how we applied those principles specifically to our sprinting, jumping, and lifting.

After warming up as I detailed in the second post of this series, we moved into either speed work or plyometrics. We did one or the other every single day in small, intentional doses—enough to stay fresh while keeping the CNS sharp and responsive.

Speed

To develop speed, we kept it simple: games, races, and forms of tag to incentivize running fast—because who doesn’t run their fastest when being chased or trying to win a race?

The key was always keeping these portions short and allowing enough rest to ensure we were truly training maximum speed (around 15 minutes at most). Most importantly, we never ran for conditioning, we only ran for speed. Conditioning always came naturally through the basketball being played.

Depending on the goal, we started races in a variety of ways:

- Reacting to game-like visual cues (the opponent starting)

- Reacting to less representative visual cues (the drop of a ball)

- Reacting to audio cues (“Go!”)

And we ended them in various ways too:

- Running through a line or knocking down an object (full speed)

- Picking up an object before the opponent (accelerating, then decelerating to collect it)

I’ll be sharing more speed competition ideas in future posts in the vault, but the possibilities here are endless.

Plyometrics

For plyometrics, our goal was to train athletes to jump in different planes and in different ways. Again, these portions were short and quick.

Dunk Contest

We held different dunk contest days—some focused only on strong-leg jumps, others only on weak-leg jumps, and some alternating between the two. Players initially identified their preferred way of jumping (one foot or two feet, left foot or right foot), and we used that awareness to challenge them outside their comfort zone.

Each day, players chose an initial level they felt was ideal for them. The six levels were: touch the net, touch the backboard, touch the rim, dunk a tennis ball, dunk a dodgeball, dunk a basketball.

They did two dunks per set. If a player was successful on both attempts, they moved up a level. If a player was unsuccessful on both attempts, they moved down a level. If a player was successful on one attempt, they stayed at the same level.

Everyone thinks dunking is cool. By turning it into a game with levels, players have fun competing and watching others while getting in plyometric work—often without even realizing it.

Obstacle Course

Our other plyometric training method was an obstacle course—designed and set up by the players themselves. They could choose any props from around the weight room and arrange them however they wanted, creating a unique course each time.

There’s room for improvement in the plyometric training described above, since these actions are scripted—before a dunk, the athlete already knows how they’re going to jump, and before an obstacle course run, they know the sequence of jumps. Still, I believe these activities provided value, building explosiveness, variety in movement, and a fun, competitive element to training.

Weight Room Lifts

For our lifts, I co-created a workout plan with a recent four-year varsity player—a runner and master of movements—who managed to gain 50 pounds during his high school career without losing his cat-like traits.

We trained three days per week: an upper body day, a lower body day, and a day we called Elite Athlete Day (filled with weighted plyometrics, banded jumps, sled pushes and pulls, and similar explosive movements). One specific lift we emphasized was the hang clean. Hang cleans translate directly to jumping, sprinting, and other cat-like movements—they target similar muscle groups, use a quick snapping motion, and demand coordination across the entire body.

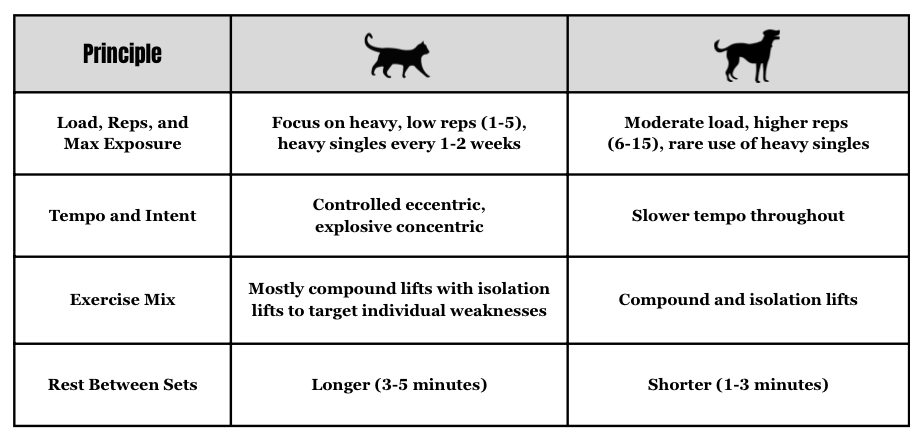

There are key differences in the way cats lift compared to dogs. Here’s a sheet outlining those differences:

Related Resources:

By sprinting, jumping, and lifting in this way, we were able to sharpen the cat-like traits that translate directly to winning basketball games.

PART ONE: Variability is key (an overview)

PART TWO: Variability is key (warmups)

PART THREE: Variability is key (sprinting, jumping, lifting)

PART FOUR: Variability is key (shooting)

PART FIVE: Variability is key (looking ahead)