Conceptual handoffs, the how and why

In a recent post, I broke down the components of great, modern offense. Now, I will begin to specifically explain how we’ve combined ball movement, player movement, actions, continuity, and advantages to produce spacing, opportunity, complexity, flow, and efficiency.

Building an offense based on handoffs

We’ve tried to play without on-ball actions in the past, but against the bigger, more athletic teams we face (especially in neutral half-court settings), we struggled to generate consistent advantages. Because our strengths are shooting, speed, and IQ, we doubled down on more ways to make our games a track meet rather than a wrestling match—and handoffs fit perfectly.

Handoffs maximize our players’ strengths, allowing shooters to become more effective playmakers, create advantages, and generate 2-pointers. By infusing handoffs into our offensive framework, the hope is that our players go from hard to guard individually to impossible to guard collectively, as the whole becomes greater than the sum of its parts.

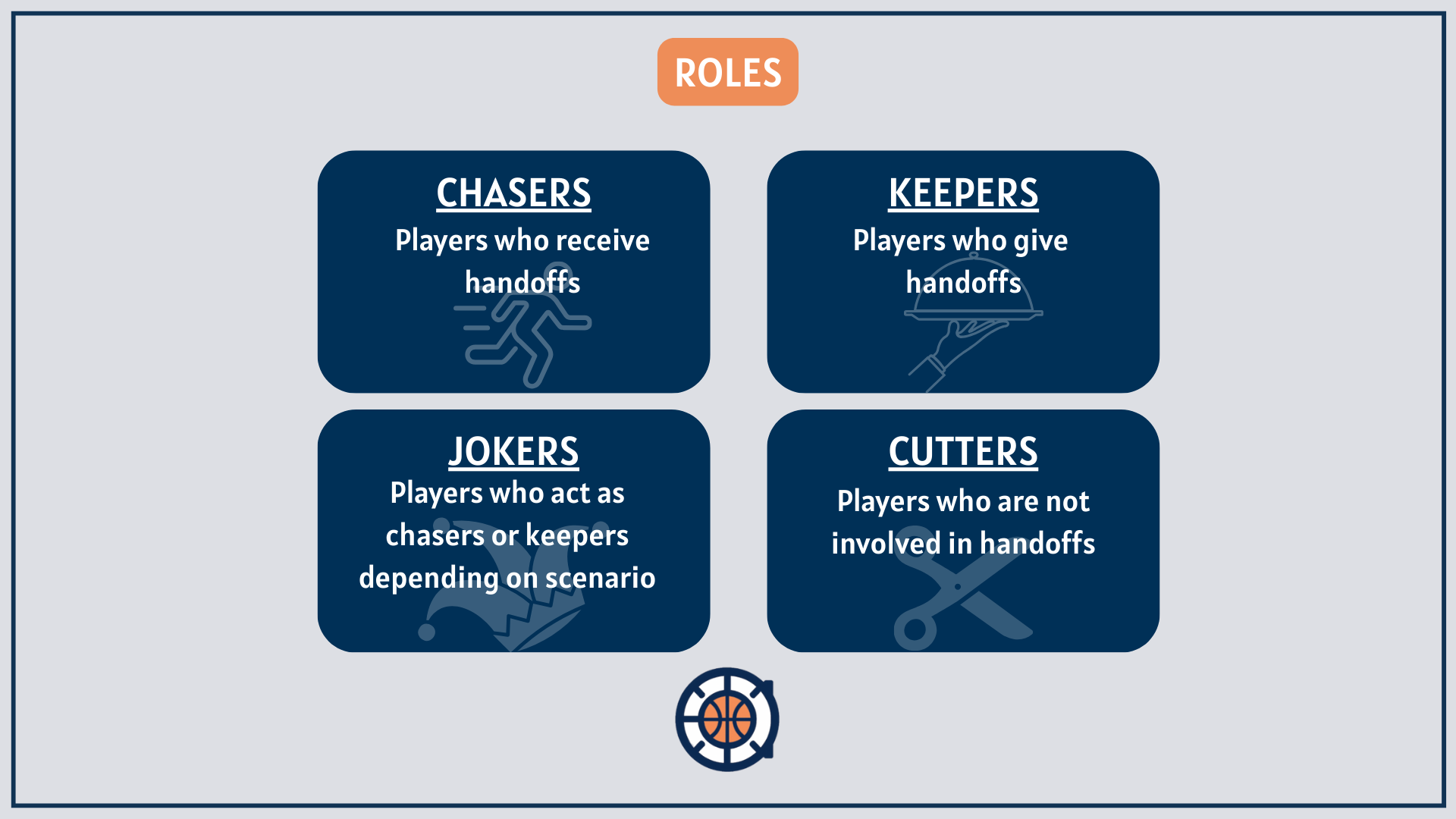

Roles that allow handoffs to emerge

We never call for a handoff because that would make it too predictable. Instead, it emerges from our automatics: clearly defined player roles provide the structure and naturally trigger the action.

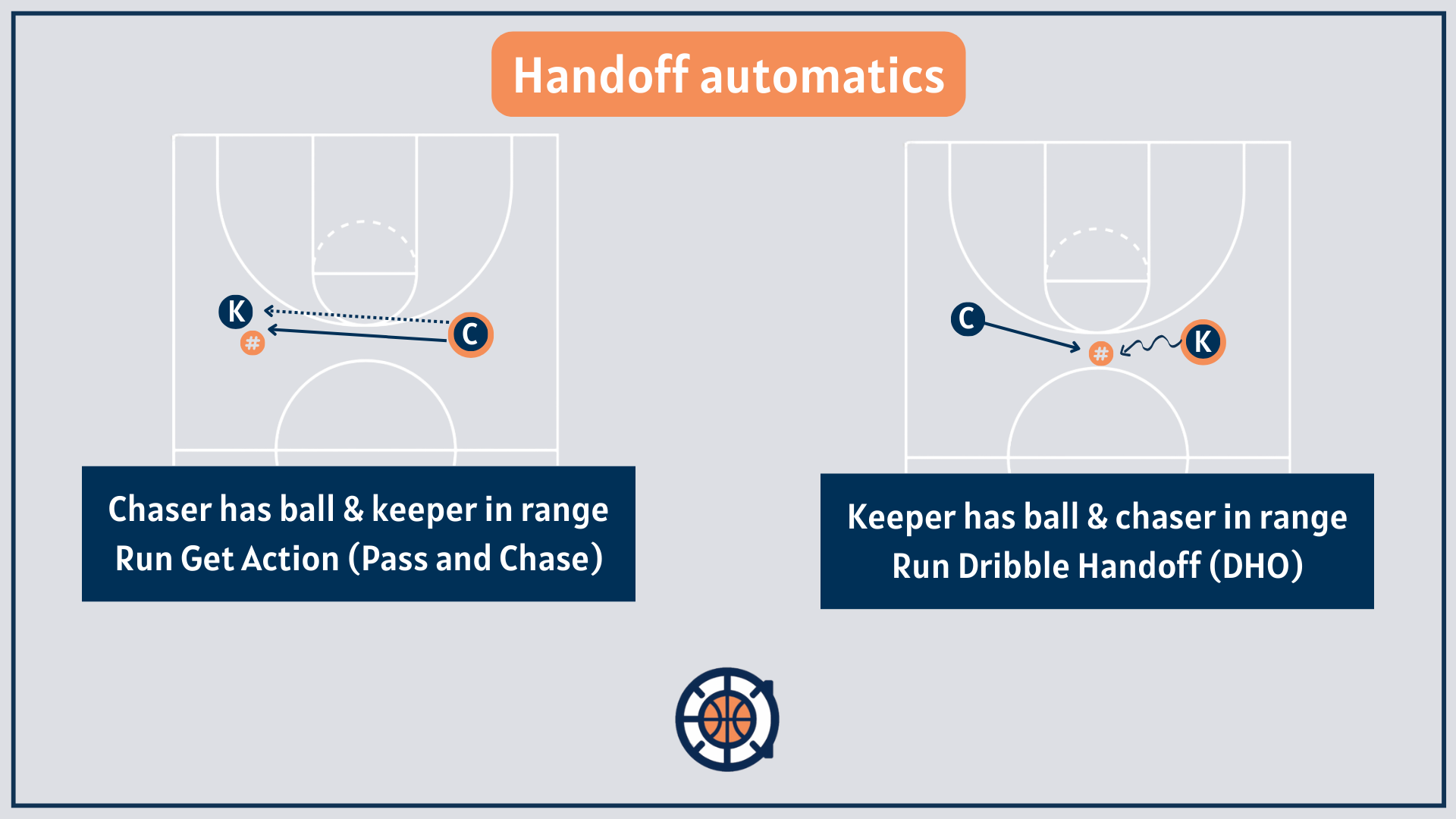

So based on these roles, the automatics become:

- Keeper with the ball: look for a dribble handoff (DHO) with a chaser

- Chaser with the ball: look for a Get action with a keeper (pass and chase it for a handoff)

- Cutter with the ball: look to attack, pass-and-cut, or pass-and-zoom (DHO into a ball screen)

As Caitlin Cooper noted about the Pacers, there’s “variety to how each of those actions gets expressed by the players involved—and, sometimes, very specifically, because of which players are involved.” That’s the point: our handoffs are unscripted (at least to the defense) and occur organically with different pairings, from different angles, in different sequences, and with different strengths and styles based on who’s involved. We empower players to choose the best strategy in the moment, and that constant, context-driven decision-making makes defensive communication and execution hard. We are making a bet that the defense can’t guard it perfectly every time, especially as quickly as it can develop.

Coaches talk about “multiple sides” and “reversals” all the time to get great shots. Our spin is to stack actions until the defense screws up (or like Steve Kerr says, everything comes out in the wash).

It’s easy to run a hodgepodge of unrelated sets or continuous, repetitive motion offense. It’s harder (but far more rewarding) to build a personnel-based system where automatics create the action to get the right players involved at the right times. This lets players and coaches focus on their quality of play (the read, the speed, the counter) rather than remembering plays. As Jimmy Tillette puts it: “The Dallas Cowboys had five plays but 25 formations. It looks like it’s complex, but it’s really not that complex. They all end the same way, they just end from a different angle.”

How handoffs make it a track meet

Handoffs work because their effectiveness is tied to the separation the chaser and keeper create from their defenders. Put a good player into this action with some separation and the defense’s urgency naturally spikes, opening passing, driving, and shooting angles. We prefer handoffs over traditional pick-and-roll because the ball handler can gain this separation before the action begins (and the separation doesn’t have to be created with the dribble—which demands a higher level of on-ball creation skill).

There are also clear speed-based counters when defenses get physical or aggressive—counters I'll detail more in the next post on specific handoff teaching points. In general, chasers can answer with quick, sharp change-of-direction cuts, while keepers treat slips as a race to the rim (holding an advantage because they know when the race starts and the defense does not).

And all of that puts defenders in chase mode. That’s exactly where players who take pride in both off-ball execution and on-ball creation do the most damage—the Steph Curry model that Steve Kerr highlights. Richard Jefferson echoes similar thoughts, noting that defenses aren’t prepared for the energy and constant movement Curry sustains every game. Our handoff framework demands (and spotlights) that blend, turning it into a constant challenge for the defense and making these actions nearly impossible to guard.

In my next post, I'll discuss specific teaching points for the handoffs in our conceptual offense.